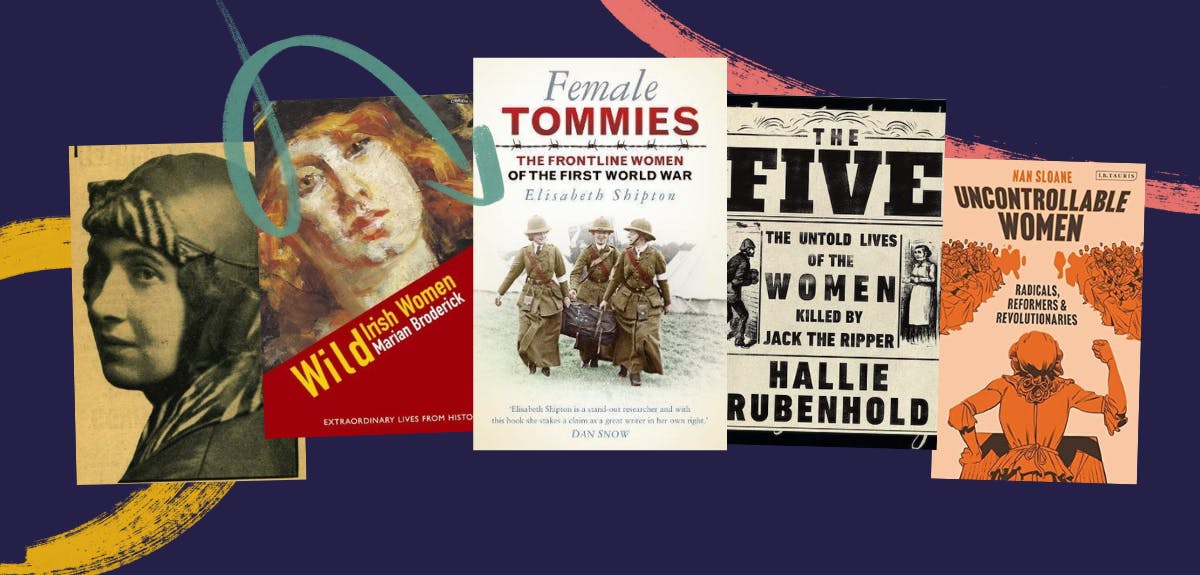

Discover female trailblazers with these six books on women's history

8-9 minute read

By Mary Mckee | March 16, 2023

Findmypast’s women’s history expert Mary McKee has created a list of exciting and revealing books about women’s history, ranging from radical women of the French Revolution to criminal Irish female emigrants in North America. The list will inspire you to look closer at the women in your family tree and dive deeper into the records to uncover more rich stories.

I have pulled together some of my favourite and most interesting books about women in history. This is by no means an exhaustive list. There is so much out there to read, and every year even more incredible works are being published.

In this list, I’ve tried to go beyond popular history, past the stories of royals and suffragettes that we know too well. Often in history, women’s contributions have been overlooked. It was the kings and the male politicians who wrote the narratives. In some cases, women’s achievements were even attributed to men. Years of unpaid labour and childbearing have been ignored.

At Findmypast, we believe that every story is important and every person in our family tree has made an impact on our lives.

I hope these publications inspire you to take a second look at the amazing women in your own tree. Although the list focuses on British and Irish history, there is so much more to explore as you branch out into the field of women’s history.

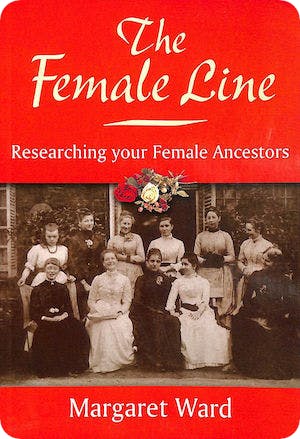

1. The Female Line: Researching Your Female Ancestors by Margaret Ward

Could we really talk about women’s history, without first talking about the women in your family tree?

Margaret Ward describes this as a ‘book of possibilities’. She attempted to answer the questions in between the civil registration certifications and census records. What was life really like for our female ancestors, given that so much of their private lives was unrecorded?

In 8 chapters, Ward has pulled together lists of great resources and practical advice for how to discover more about your ancestors. She focuses on the time period 1800 to 1945, and begins with the first challenge of tracing your female line given the name changes.

The other chapters tackle photographs, criminal records, work, women, war, marriage, and those old relicts. Relicts comes from the Latin ‘relinquere’ meaning ‘leave behind’ referring to a widow, but as Ward puts it, the word is too close to relic to feel comfortable.

In the chapter about photographs, Ward guides us through ways to find out what your ancestor looked like.

These many lines of enquiry within Margaret Ward’s short book provide a great basis for your own research, and can inspire you to look at records or books that you hadn’t considered before.

2. The Five by Hallie Rubenhold

This bestseller and winner of the Baillie Gifford Prize for non-fiction is a must read. Rubenhold has been able to unearth the lives of the five women who were victims of the Whitechapel murders. It is a radical retelling of the Jack the Ripper story from the perspective of the female victims.

Too much time has been spent speculating about the perpetrator of these crimes - less time has been spent considering who the women were. One main reason for this was because they were considered ‘only prostitutes’. Rubenhold proves that not all the victims were sex workers but were women living in extreme poverty and today would be considered rough sleepers.

Rubenhold’s incredible research reveals the complex lives of these women from their early years until those gruesome nights in Whitechapel. She uses resources that we hold dear in family history: newspapers, police reports, workhouse records, census records, immigration lists, and so much more.

The amount of research dedicated to each woman is inspiring for those researching their female ancestors, especially those who were working class. It's amazing to see how much Rubenhold was able to uncover. She truly humanised the Whitechapel murders victims and brought forth a brand new narrative.

After reading The Five, you can delve into the original sources yourself by searching through the British census records or reading contemporary newspaper reports of the Whitechapel murders.

3. Bad Bridget: Crime, Mayhem and the Lives of Irish Emigrant Women by Elaine Farrell and Leanne McCormick

Bad Bridget is the most recent publication on this list. It was written after years of research into the criminal Irish women in North America from 1838-1918.

Between 1815 and 1915, over 7.5 million people emigrated from Ireland. One in three emigrants were women, and that increased to one in two between the years 1845 and 1885.

Many of us are familiar with the inspiring immigrant story of landing in a new country with very little and building a new life through hard work. But what about the lives of those hundreds of thousands who lost their jobs, haunted the pubs, or were considered immoral? These are the women the authors have dubbed ‘Bad Bridget’. This work is showing for the first time the underbelly of Irish emigration.

The criminal statistics are staggering. Criminal activity is of course part of women’s history. What the authors found were striking numbers, such as that 37.8% of the women admitted to the House of Correction in Boston were Irish from 1882 to 1905. They reveal similar numbers in New York and Toronto.

The ‘criminals’ have a wide range of backgrounds – urban and rural, Catholic and Protestant. Even the ‘type’ of criminal varies. The authors explore the lives of those who commit first time minor offences and others who continue to become career criminals. There is a broad spectrum of crimes explored, including theft, prostitution, public drunkenness, child neglect, and even murder.

Each chapter looks at different cases, such as that of 18-year-old Ellen Nagle who was arrested, charged, and imprisoned under the Massachusetts offence of being a ‘stubborn child’. Nagel spent 12 months in prison on this charge. Others were punished for being wayward or incorrigible.

The incredibly detailed research provides us with insight into the women’s relationships with their family, in North America and back in Ireland. In some cases, we even follow their journey from Ireland to North America.

The authors layer in historical context along the way, like the changes to the juvenile system or marriage laws that impact emigrant lives. Ellen Nagle is traced for ten years, from the time she was living with her parents and the school she attended, then when she ran away from home, followed by her arrest then release in 1904. The authors even continue the full story to when Nagle is married in 1906 and in 1910, she is listed in a tenement building.

Bad Bridget offers a brand-new perspective about the lives of female immigrants in North America.

4. Wild Irish Women: Extraordinary Lives from History by Marian Broderick

I bought this book over 15 years ago, and it inspired me to study Irish women’s history. Broderick has gathered the stories of over 70 inspiring women from history. Some you may have heard of before, but many you haven’t. The short biographies are a great introduction to these amazing lives.

We are introduced to Kit Cavanagh, the 18th century soldier. After her husband was forcibly conscripted to fight for William III in Holland, she followed him and joined the Duke of Marlborough’s infantry. She served with the army from 1693 to 1706.

During that time she was wounded, taken prisoner, returned to the battlefield and eventually found her love. But even after that, she continued to serve with the army. In 1706, after being injured again, she was discovered to be a woman, but instead of being admonished she became a celebrity. She lived her final years as a Chelsea Pensioner.

You will also discover the story of Peig Sayers, one of Ireland’s greatest storytellers and contributor to Irish folklore. Without her amazing gift of storytelling, much of Ireland’s folklore would have been lost. Another worth mentioning is flying pioneer Lady Mary Heath, who you can discover in Findmypast's newspaper collection.

There’s also Sarah Purser, a portrait painter who painted some of the best-known national figures. Her success allowed her to financially support the arts, and she went on to become the first female member of the Royal Hibernia Academy.

These women were ahead of their time. Broderick’s fluid prose makes each biography interesting and easy to consume. This book is only a stepping stone to invite you to uncover more about their lives.

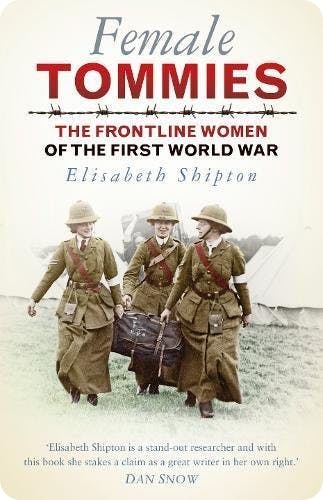

5. Female Tommies: The Frontline Women of the First World War by Elisabeth Shopton

The book goes beyond the well-known home front to consider what women achieved on the frontline. Elisabeth uses diaries, letters and memoirs to tell these extraordinary stories. The book is organised into themes of women in the trenches, medicine and espionage. These are followed by chapters on women in Russia, the American military, and the British services.

You will learn about the Dorothy Lawrence, the 18-year-old women who in 1915 impersonated a British soldier to get closer to the frontlines in France. She wanted to become a war correspondent and thought this would be a way to prove herself. When she was revealed, her story became an embarrassment to the British army and had a counter effect on her goals.

There is also the story of Dr Elsie Inglis of Edinburgh, a physician who enlisted in 1914 and applied for the Royal Army Medical Corp, but was told ‘my good lady, go home and sit still’. Nevertheless, she persisted and founded the Scottish Women’s Hospitals.

Shopton doesn’t only focus on British women, but features women of various nationalities. Draga Liocic, for example, was the first Serbian woman to qualify as a doctor and served during the Serbian-Turkish war, the Balkan Wars, and the First World War.

The chapter on women involved in resistance movements and espionage is amazing, particularly when you consider these are only the stories we know. There are countless others whose names were never recorded. For example, we learn about the story of Luisa Zeni, who was recruited as a spy in Italy. She crossed into Austria and posed as a nurse. When she was discovered, she managed to escape before being executed.

6. Uncontrollable Women: Radicals, Reformers and Revolutionaries by Nan Sloane

This book is the perfect example of going beyond popular history. Sloane has studied a period of history that is often overlooked in women’s history - the period from the outbreak of the French Revolution in 1798 to the Great Reform Act of 1832.

It looks at those women who fought against the rules laid down for women by religion, society, and legislation. Sloane doesn’t skirt over the fact that many of these people were flawed, and carried with them racist and homophobic views. It is important to look at all aspects of a person’s life and acknowledge the good with the bad, as no-one in history is perfect.

Sloane has broken through the class lines to bring forth stories of working-class women which are often forgotten, because of the lack of documentation.

The book is organised into four parts. The first focuses on radical middle-class women in the revolutionary times of the 1790s. The second part looks at working class women fighting for reform in their communities between 1812 and 1819. In the third section we are introduced to the lives of free thinkers and ‘infidels’ of the 1820s. Finally are those radical women who encouraged ideas of socialism and women’s political rights.

If you are looking for a book that will challenge your thoughts about women’s role in history this, is it.

Discover the trailblazers in your family

What have you uncovered about the strong women in your family?

We'd love to hear their stories. Tell us directly, using the form above.

Related articles recommended for you

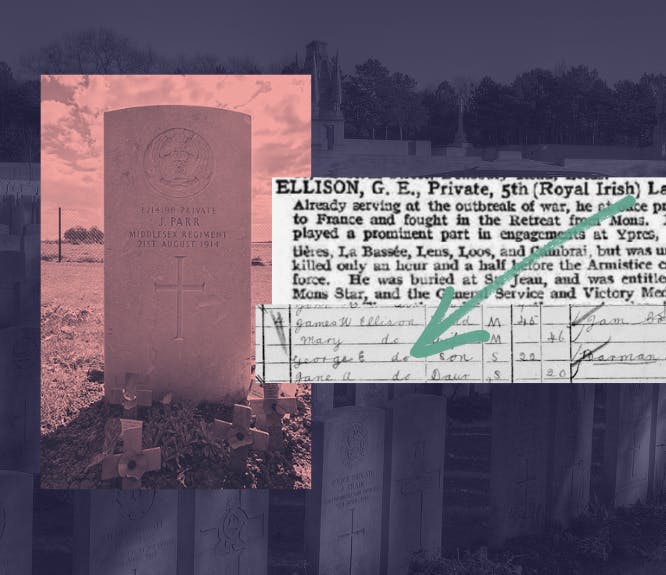

Remember their story: the first and last British soldiers killed in the First World War

History Hub

Who Do You Think You Are? Series 21: here's what you missed

Discoveries

We discovered German and Scottish roots in Donald Trump's family tree

What's New?