Discover the remarkably rich history behind Irish diaspora through the centuries

6-7 minute read

By Brian Donovan | February 24, 2023

In-house expert Brian Donovan discusses his favourite publications for understanding the circumstances that surround generations of Irish migration.

Every St. Patrick’s Day we are reminded that while less than seven million people live on the island of Ireland, more than 90 million claim Irish ancestry globally. That’s a huge number.

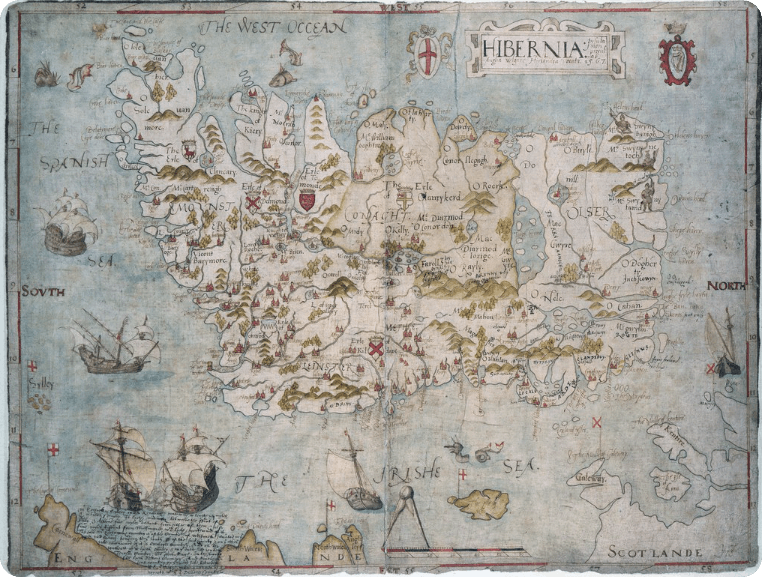

A 1567 map of Ireland by John Goghe.

The story of how that came to be is multi-layered, rich and diverse. It’s a record of migration from the earliest times for a multifarious range of reasons and is impossible to simplify into a single thread. Most people usually only know one of the many migrations from Ireland, most commonly the flight during the Famine (1845-52).

But while that episode continues to haunt the Irish landscape, it was just one thread in the tapestry of Irish diaspora.

In one way or another I have been studying Ireland’s historical migrations all my life, including helping set up EPIC The Irish Emigration Museum in Dublin in 2016.

EPIC The Irish Emigration Museum, Dublin.

Many years ago, I digitised the wonderful 1890 edition of The Irish Emigrant's Guide for the United States (available free at the Irish Family History Centre), a practical guide for those arriving in America. It describes how to secure employment on arrival, get a bank account, find accommodation, and more including notes on each individual state.

It's extraordinary reading the actual guidebook that immigrants used to get started.

Using contemporary publications to understand Irish diaspora

There has been a huge amount of scholarship around Irish migration to America. In 2006, Glucksman Ireland House, NYU, picked apart the various themes of Irish migration to America and the subsequent Americanisation of the Irish in Making the Irish American: History and Heritage of the Irish in the United States, edited by Professors Joe Lee & Marion Casey.

Making the Irish American book cover.

It’s a big book, packed with specialist articles on the Scots-Irish, Presbyterians, Catholicism (Irish and American) and religious rivalry between and within the community. It discusses the place of the Irish in the labour movement, politics and the impact they had on Irish nationalism both in the US and back at home.

But despite dealing at length with the positive stories of Irish involvement in music and sports, the book does not flinch from the darker side of the Irish experience, including the bigotry they were faced with and the frequent bouts of racist violence they themselves perpetrated on others.

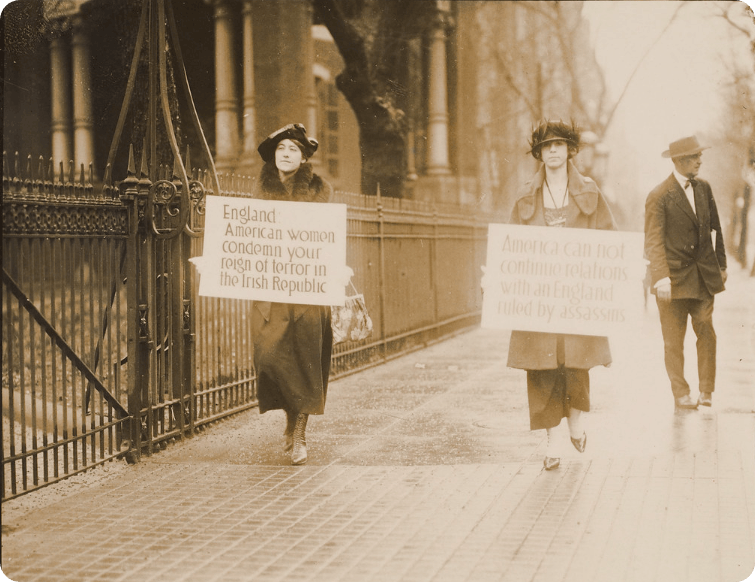

Two American-Irish women protesting England's treatment of the Irish at the British Embassy, Washington, 1920.

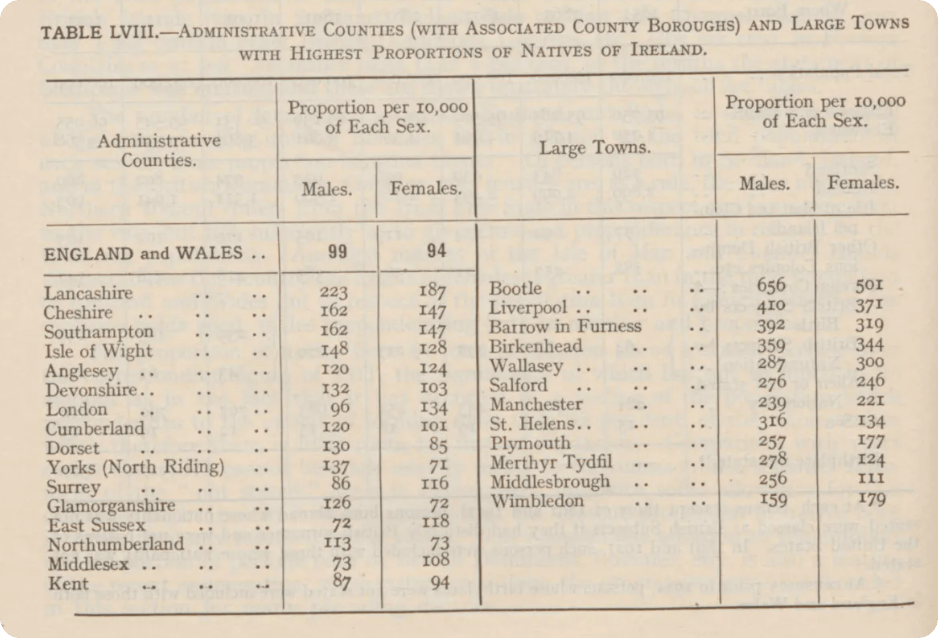

While Irish migration to America is universally acknowledged, the most likely destination for Irish emigrants was Britain. The Industrial Revolution desperately needed labour, and the Irish answered that call in droves. In fact it has been estimated that today 1 in 4 people in Britain have an Irish grandparent.

A table showing the counties with the largest proportion of Irish residents, as reported in the 1921 Census of England and Wales.

However, unlike those that settled in America, the Irish that spread roots in England, Scotland and Wales tended to lose their national identity quicker, and more rapidly merge with the communities they settled amongst.

This - and much more - is comprehensively covered in the excellent book by Professor Donald MacRaild, The Irish Diaspora in Britain 1750-1939 (2nd edition 2010), who elegantly summarises and collates the research that has been published across hundreds of specialist studies.

The Irish Diaspora in Britain 1750-1939 book cover.

Unusually, he also address the Irish Protestant community and showed how they maintained a separate identity.

As well as this, his work shows how much the story has improved from the Catholic nationalist nostalgia evident in older works, like John Denvir’s 1892 book The Irish in Britain: From the Earliest Times to the Fall and Death of Parnell (available free on archive.org).

Irish settlement worldwide is also part of the uncomfortable story of the British Empire. Ireland was, after all, a constituent part of the United Kingdom from 1800, and politically controlled by Britain for centuries before that date.

A photograph of barracks in a British Army garrison in Munster, Ireland, taken in the early 1920s.

Uniquely, the Irish story is both as victims and perpetrators of Empire. Naturally, we feel more comfortable with the former than the latter, but both sides are equally true.

This is explored with great depth and nuance in Nicholas Canny’s first chapter in Kevin Kenny’s masterful Ireland and the British Empire. Keith Jeffery’s comprehensive volume of essays, ‘An Irish Empire’?: Aspects of Ireland and the British Empire delves ever further into these complexities.

Ireland and the British Empire book cover.

Reading these, I quickly realised how messy the Irish entanglement in Empire was, made even more complicated by the active British promotion of the Irish Catholic church in their colonies as a loyal ally. This is revealed in Colin Barr’s, Ireland’s Empire: The Roman Catholic Church in the English-speaking world, 1829–1914 (Cambridge).

As family historians, of course, we always try to understand these big themes through individual stories. But there are so many individual stories it can be difficult to know where to start. One book that sticks with me though is a volume of reports Mr. Tuke's Fund for Assisted Emigration 1882-5 (available free at the Irish Family History Centre).

The Irish Family History Centre, Dublin.

This was a philanthropic fund set up by the Quaker James Tuke to help over 9,000 people leave parts of the most impoverished regions of the west of Ireland to go to America.

Not only does the book list all the emigrants, their addresses in Ireland and where they moved to, but they also printed their letters home detailing what life was like in their new homes.

One wrote from Ontario, Canada:

"'I was only twenty minutes at the hotel before I was engaged on a farm. Wages are big here; this is a fine country. Spring is just commencing. My parents have got a house here, and father is working on the railway.'"

Letters and personal memoirs are also the focus of a modern scholarly work by Kerby Miller, Irish Immigrants in the Land of Canaan 1675-1815, on the earlier period of migration to America, more likely from the eastern half of Ireland.

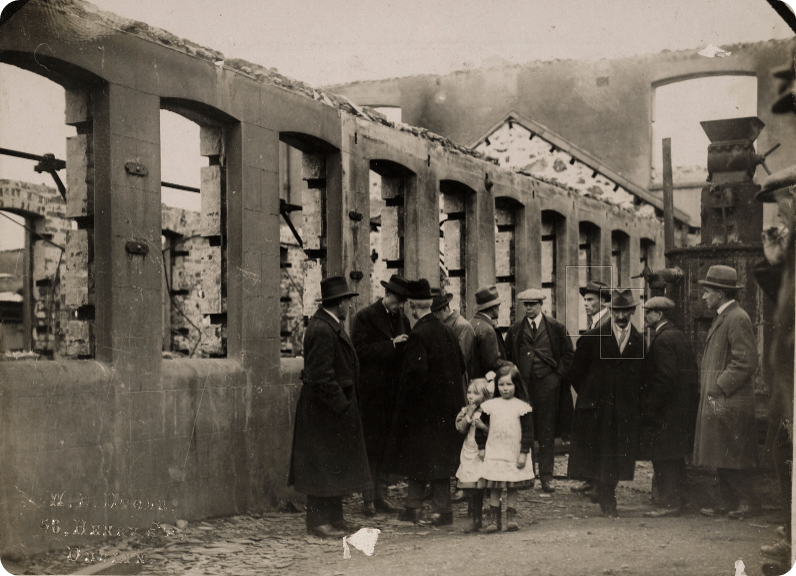

The American Committee for Relief inspecting the ruins of Balbriggan in eastern Ireland, c. 1921.

But the book is far more than a collection of interesting historical documents. Instead, Miller uses the documents as a touchpoint to address a range of big social questions, settlement patterns, and political issues.

More importantly, the book transformed our understanding of the scale of Irish migration in the 18th century, showing how more than 400,000 arrived.

The truth behind Irish migration

It's not easy to recover the truth from the narrative that has become popular in many parts of the world. Many descendants of Irish emigres like to wrap themselves in the comforting blanket of the rags-to-riches tale, or recount the ancient wrongs done to innocent people.

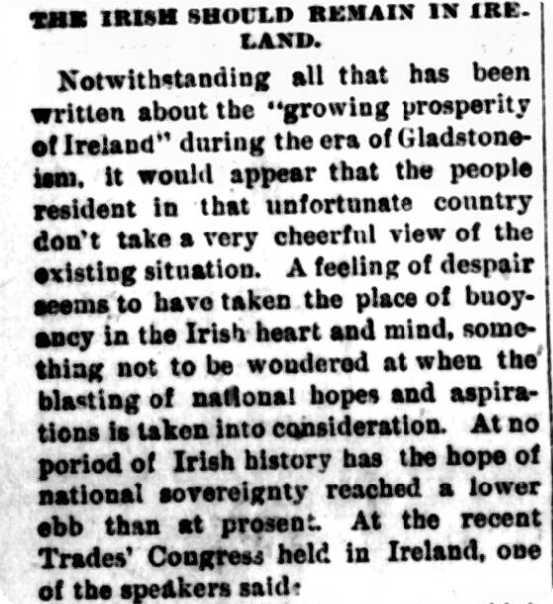

An article titled 'The Irish should remain in Ireland', published in American-Irish newspaper the Chicago Citizen, 1895.

Sometimes the stories are true, but more often its selective memory. What families choose to remember is usually only what was talked about. Irish immigrants, like those from any other country, had much they did not want to remember and little time to put their own experience in any sort of context.

In that case, it is up to us, family historians and social historians, to recover the individual stories and place them into the flow of the migration story from Ireland.

If you want to learn more about researching your Irish heritage, delve into our top five books that inspired the Catholic Heritage Archive here at Findmypast.